Students write a question on an index card and give it to a partner at their table to answer. A trading card format engages students in the questions. Remind students that the answers need to be supported by evidence in the text. Later in the year, students can begin to develop their own questions to ask their peers. For example, when learning about character traits, students were asked to show what the protagonist thought, said, or felt, while rooting their responses in evidence. To deepen comprehension, students can engage in discussion around what they have read. To make sure that readers of all levels can participate, the questions should range from simple, such as “What is the title of the article?” to more complex, such as “Who is the audience for this article and why?” I ask specific students for responses.

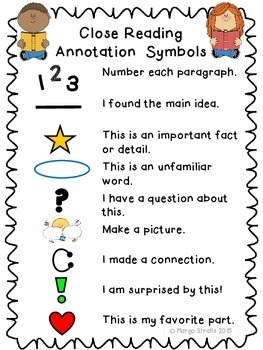

Encouraging Critical Questionsįinally, the students answer questions I create about the text. When students are not racing to find an answer, they can critically explain why their answer makes sense in the context of what they are reading. Annotating text encourages students to slow down and have meaningful interactions with their peers. Strong readers may complete this task by themselves or work with peers who need support as long as clear expectations are put in place. As the year progresses, some of the steps can be combined, and students may begin to annotate the passage earlier in the process. I wonder what it means.” We then put a question mark by the word. I model my thinking during reading by pausing and noting, “I have not heard the word ‘extinction’ before. After noting the vocabulary I want to revisit, we define the meaning of the text.įollowing the independent read, we read the passage again as a class, pausing to annotate. The words that need to be retaught are often content specific and essential for students to understand. Their feedback informs what vocabulary I can teach in an upcoming lesson. I ask students to share unknown words with the class and mark them on my own text. This helped students understand how a text works to provide a logical flow of information.Īfter reading the passage together, students reread it independently and put a box around unfamiliar words. Students wrote down the date and the event that occurred. When we read an article about Ellen Ochoa, the first Hispanic woman to go into space, we used dates provided in the text to sequence her life using sticky notes. This print in bold serves as a clue to let us know the topic of each paragraph. When we read an article on weather, we discussed how headings use bold print. When we encounter a word in bold, we discuss how bold words have a specific purpose. I devise a mini-lesson on the importance of each key term. Together, we mark the key terms with a blue box, and I explain why we are making this mark. A common key for the color coding can be presented as a visual at the front of the classroom so that the whole class uses consistent marks.Īt the beginning of the year, we read the text together-first for fluency, or, as I told my students, to “get mouths familiar with the words.” Then we read the passage again with the goal of finding key terms such as numbers, dates, and names of places. Initially, color-coding annotation provides visual cues for students. When reading, students can use pencil marks to annotate the text. As a prereading strategy, students can make predictions about what the text is going to be about based on context clues like the title and pictures. Once a purpose is set, number each paragraph of the article to allow students to cite their sources and track their reading.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)